Esta entrada es blingüe, desplazarse hacia abajo para acceder a la versión en español

Included in The Complete Father Brown Stories by G. K. Chesterton, edited and with an Introduction by Michael D. Hurley. Penguin Classics, 2012. Book Format: Kindle Edition. File Size: 989 KB. Print Length: 868 pages. ASIN: N/A. ISBN: 978-0-141-95993-1. The Innocence of Father Brown is the first short story collection by G. K. Chesterton featuring his clerical detective. The twelve stories that make up this collection were published separately in The Saturday Evening Post and The Story-Teller between July of 1910 and June of 1911 before being gathered in book form in 1911 by Cassell and Company Ltd., London, and by John Lane Co., New York.

Summary: Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He features in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936. Modest in appearance, Father Brown has a mysterious ability to see into the bleak abyss of the criminal mind. This skill, according to Father Brown himself, comes from his experience as a priest and a confessor. Absolute rationality is another one of his characteristics. He always seeks the natural explanation for any kind of phenomenon. Chesterton loosely based Father Brown on Father John O’Connor (1870 – 1952), a parish priest in Bradford, Yorkshire. It should be noted that, contrary to what many people believe, Chesterton was not a Catholic at the time he wrote the first Father Brown stories from 1910-1914. That conversion wouldn’t happen until the 1922.

Summary: Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He features in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936. Modest in appearance, Father Brown has a mysterious ability to see into the bleak abyss of the criminal mind. This skill, according to Father Brown himself, comes from his experience as a priest and a confessor. Absolute rationality is another one of his characteristics. He always seeks the natural explanation for any kind of phenomenon. Chesterton loosely based Father Brown on Father John O’Connor (1870 – 1952), a parish priest in Bradford, Yorkshire. It should be noted that, contrary to what many people believe, Chesterton was not a Catholic at the time he wrote the first Father Brown stories from 1910-1914. That conversion wouldn’t happen until the 1922.

The Innocence of Father Brown, a collection of twelve mysteries stories, appeared in 1911. Whereas Sherlock Holmes specialized in deductive reasoning and used scientific aids – fingerprinting, microscope, and magnifying glass – investigate crime, Father Brown is intuitive. He relies on philosophy and his knowledge of sin” (Martin Edwards at The Golden Age of Murder, Collins Crime Club, 2016).

The twelve stories that make up The Innocence of Father Brown are:

“The Blue Cross” (First published as “Valentin Follows a Curious Trail”, The Saturday Evening Post, July 23, 1910; The Story-Teller, September 1910) Aristide Valentin,head of the Paris police, has just arrived in London to arrest Flambeau. It is suspected that Flambeau, the most famous criminal in the world, is in London where he expects to commit a crime, taking advantage of the confusion created by the large crowd of people attending the celebration of the Eucharistic Congress on those days. Flambeau is a master of disguise and can impersonate anyone, although he can’t hide his large stature. “Valentin had learned by his inquires … that a Father Brown from Essex was bringing up a silver cross with sapphires, a relic of considerable value, to show some of the foreign priests at the congress.” What had the stealing of a blue-and-silver cross from a priest from Essex to do with chucking soup at wallpaper? What had it to do with calling nuts oranges, or whit paying for windows first and breaking them afterwards?

“The Secret Garden“(First published September 3, 1910 in The Saturday Evening Post; The Story-Teller, October 1910) In a continuation of the previous story, the scene moves to Paris. Aristide Valentin, the head of the French police, has organized a dinner party at his house. The guest of honour is Julius K. Brayne, an American billionaire who is considering donating a large sum to the Catholic Church. The party is interrupted when one of the guests finds a corpse in the garden with its head cut off. No one is able to identify the corpse. In addition, the garden has high walls, it has no gates and there is no other way to enter or leave the garden without being seen other than through the house and the gate of the house had been diligently guarded at all times by a servant. Under such circumstances it is as strange to establish the victim’s identity as it is to find out how he got there unseen. All the guests are very respectable people and, except for one, all have firm alibis. The only exception is Brayne himself, who was seen rushing out of the house just before the body was found. All suspicion falls on him, but the story takes an unexpected turn when another headless body is found floating in a nearby river, and his head turns out to be Brayne’s own.

“The Queer Feet” (First published October 1, 1910 in The Saturday Evening Post; The Story-Teller, November 1910) “If you meet a member of that select club, “The Twelve True Fishermen,” entering the Vernon Hotel for the annual club dinner, you will observe, as he takes off his overcoat, that his evening coat is green and not black. If (supposing that you have the star-defying audacity to address such a being) you ask him why, he will probably answer that he does it to avoid being mistaken for a waiter. You will then retire crushed. But you will leave behind you a mystery as yet unsolved and a tale worth telling. … If (to pursue the same vein of improbable conjecture) you were to meet a mild, hard-working little priest, named Father Brown, and were to ask him what he thought was the most singular luck of his life, he would probably reply that upon the whole his best stroke was at the Vernon Hotel, where he had averted a crime and, perhaps, saved a soul, merely by listening to a few footsteps in a passage. He is perhaps a little proud of this wild and wonderful guess of his, and it is possible that he might refer to it. But since it is immeasurably unlikely that you will ever rise high enough in the social world to find “The Twelve True Fishermen,” or that you will ever sink low enough among slums and criminals to find Father Brown, I fear you will never hear the story at all unless you hear it from me.”

“The Flying Stars” (First published May 20, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post) “‘The most beautiful crime I ever committed,’ Flambeau would say in his highly moral old age, ‘was also, by a singular coincidence, my last. It was committed at Christmas.” “Flambeau would then proceed to tell the story from the inside; and even from the inside it was odd. Seen from the outside it was perfectly incomprehensible, and it is from the outside that the stranger must study it.” The plot revolves around The Flying Stars, three brilliant diamonds, whose fame has spread throughout England, that have been purloined during an innocent Christmas pantomime.

“The Invisible Man” (First published Jan. 28, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post, later in Cassell’s Magazine, Feb 1911) Laura Hope tells John Turnbull Angus about her complicated love life. A year ago, while working in his father’s pub, two men proposed to her. One was a very short man named Isidore Smythe, the other, tall and skinny, was James Welkin. She didn’t find either of them attractive, but she didn’t want to hurt their feelings either. To escape this situation, she told them that she would not marry a man who had not made his way in the world and they both rushed to seek their fortune, as if they were in a silly fairy tale, in Laura’s own words. One year later, Laura runs a café, but she fears that Welkin has found her. She hears his voice from time to time when no one is around her. She has received a letter from Smythe, who is now a successful businessman, but as she reads his letter, she keeps hearing Welkin’s peculiar laugh. Angus offers to help her by putting the matter in the hands of a private detective he knows who lives nearby. The detective is Flambeau, the former French criminal master, now reformed by Father Brown. As the story progresses, Angus accompanies Smythe to his apartment and promises to return with Flambeau. Before Angus leaves, he instructs four people, a cleaner, a doorman, a policeman and a chestnut seller, to watch the entrance and notify him if anyone enters the building while he is away. When Angus returns with Flambeau and Father Brown there is no one at Smythe’s house despite the fact that the four people he asked to guard the entrance assure him that no one has entered or left the building during his absence. Shortly after, Smythe’s lifeless body is found floating in the river.

“The Honour of Israel Gow” (First published March 25, 1911 as “The Strange Justice” in The Saturday Evening Post) In this story we find Father Brown and Flambeau, now a private detective, at Glengyle Castle in Scotland to help Inspector Craven of Scotland Yard solve the strange death and secretive burial of the late earl, a secluded man who lived as a hermit with his servant, the silent Israel Gow. The Earl died and was buried in secrecy by Gow. “The last Glengyle, however, satisfied his tribal tradition by doing the only thing that was left for him to do; he disappeared. … But though his name was in the church register and the big red Peerage, nobody ever saw him under the sun.” With the sole exception of Israel Glow, his solitary man-servant. For this reason, the three of them have come to find out whether he really lived there, whether he really died there and whether Israel Gow had anything to do with his dying. “Suppose the servant really killed the master, or suppose the master isn’t really dead, or suppose the master is dressed up as the servant, or suppose the servant is buried for the master; invent what Wilkies Collins’s tragedy you like” But, how to explain the numerous and puzzling clues that accumulate behind this event so perplexing?

“The Wrong Shape” (First published Dec. 10, 1910 in The Saturday Evening Post) “Certain of the great roads going north out of London continue far into the country a sort of attenuated and interrupted spectre of a street, with great gaps in the building, but preserving the line. … If anyone walks along one of these roads he will pass a house which will probably catch his eye, though he may not be able to explain its attraction. …. Anyone passing the house on the Thursday before WhitSunday at about half-past four p.m. would have seen the front door open, and Father Brown, of the small church of St. Mungo, come out smoking a large pipe in company with a very tall French friend of his called Flambeau, who was smoking a very small cigarette. These persons may or may not be of interest to the reader, but the truth is that they were not the only interesting things that were displayed when the front door of the white-and-green house was opened. There are further peculiarities about this house, which must be described to start with, not only that the reader may understand this tragic tale, but also that he may realise what it was that the opening of the door revealed.” What follows is the investigation of the death of the celebrated poet Leonard Quinton, whose body has been found in his study, together with a note that read: “I die by my own hand; yet I die murdered!”. Until Father Brown realises that the shape of that paper was the wrong shape.

“The Sins of Prince Saradine” (First published April 22, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post) ‘When Flambeau took his month’s holiday from his office in Westminster he took it in a small sailing-boat, so small that it passed much of its time as a rowing-boat. … Like a true philosopher, Flambeau had no aim in his holiday; but, like a true philosopher, he had an excuse. He had a sort of half purpose, which he took just so seriously that its success would crown the holiday, but just so lightly that its failure would not spoil it. Years ago, when he had been a king of thieves and the most famous figure in Paris, he had often received wild communications of approval, denunciation, or even love; but one had, somehow, stuck in his memory. It consisted simply of a visiting-card, in an envelope with an English postmark. On the back of the card was written in French and in green ink: “If you ever retire and become respectable, come and see me. I want to meet you, for I have met all the other great men of my time. That trick of yours of getting one detective to arrest the other was the most splendid scene in French history.” On the front of the card was engraved in the formal fashion, “Prince Saradine, Reed House, Reed Island, Norfolk”.’ One day, while Father Brown was alone with Prince Saradine, a rowboat with six men pulled up to the wharf. One of these men identified himself as Antonelli and addressed Prince Saradine with the following words: ‘when I was an infant in the cradle you killed my father and stole my mother; my father was the more fortunate. You did not kill him fairly, as I am going to kill you. … I give you the chance you never gave my father. Choose one of the swords.’ But for Father Brown ‘…there is something wrong with this duel, even as a duel. …. But what can it be?’

“The Hammer of God” (First published as “The Bolt from the Blue” November 5, 1910 in The Saturday Evening Post). The Honourable Reverend Wilfred Bohun, a very devout man, is on his way to church for his morning prayers when he meets his elder brother, the Honourable Colonel Norman Bohun, who is by no means a devout man and is in an adulterous relationship with the blacksmith’s wife. The reverend rebukes the Colonel for his way of life while he continues to the church to pray. Barely an hour and a half have passed when he is interrupted in his prayers by the news that his brother has died. The Colonel has his skull crushed and next to him there is a small hammer.Father Brown arrives at the crime scene just as suspicion begins to fall on the blacksmith. The blacksmith, a staunch Presbyterian, has a solid alibi and firmly believes that the Colonel’s death was the result of a divine punishment. However, Father Brown is convinced that the crime was committed by the hand of man.

“The Eye of Apollo” (First published February 25, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post). Hercule Flambeau, private detective, wanted to show Father Brown his office located in a new building. The building was American-style in its skyscraper height, although it was barely finished and still understaffed. Only three tenants had moved in; the flat just above Flambeau was occupied by a fellow calling himself the New Priest of Apollo, head of a new sun-worshipped religion. The flat underneath was occupied by two sisters who offered their typing services to third parties. The other floors, the two above them and the three below were entirely bare at that time. After further description of the occupants, a tragic event occurred. Pauline Stacey, one of the typing ladies, met her death by falling down the shaft of the elevator. ‘Was it suicide? With so insolent an optimist it seemed impossible. Was it murder? But who was there in those hardly inhabited flats to murder anybody?’

“The Sign of the Broken Sword” (First published January 7, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post) Father Brown and Flambeau search among the tomb of the famous English General St Clair for clues to his mysterious death. Arthur St Clair was a great and successful English general. After splendid yet careful campaigns both in India and Africa St Clair was in command against Brazil when the great Brazilian patriot Olivier issue his ultimatum. St Clair, with a very small English force, stood up to a much larger Brazilian force, leading his men towards a certain death and, after heroic resistance, he was taken prisoner. After his capture, and to the abhorrence of the civilized world, St Claire was hanged on the nearest tree with his own broken sword hanging from his neck. Father Brown cannot understand why St Clair, one of the wisest men in the world, acted like an idiot for no reason, and Olivier, one of the best men in the world, acted like a fiend for no reason. There must be something unknown that might explain what happened.

“The Three Tools of Death” (First published June 24, 1911 in The Saturday Evening Post) ‘Both by calling and conviction Father Brown knew better than most of us, that every man is dignified when he is dead. But even he felt a pang of incongruity when he was knocked up at daybreak and told that Sir Aaron Armstrong had been murdered. There was something absurd and unseemly about secret violence in connection with so entirely entertaining and popular a figure. For Sir Aaron Armstrong was entertaining to the point of being comic; and popular in such a manner as to be almost legendary…. Father Brown had been thus rapidly summoned at the request of Patrick Royce, the big ex-Bohemian secretary. Royce was an Irishman by birth; and that casual kind of Catholic that never remembers his religion until he is really in a hole. But Royce’s request might have been less promptly complied with if one of the official detectives had not been a friend and admirer of the unofficial Flambeau; and it was impossible to be a friend of Flambeau without hearing numberless stories about Father Brown. Hence, while the young detective (whose name was Merton) led the little priest across the fields to the railway, their talk was more confidential than could be expected between two total strangers.’

“As far as I can see,” said Mr. Merton candidly, “there is no sense to be made of it at all. There is nobody one can suspect. Magnus is a solemn old fool; far too much of a fool to be an assassin. Royce has been the baronet’s best friend for years; and his daughter undoubtedly adored him. Besides, it’s all too absurd. Who would kill such a cheery old chap as Armstrong? Who could dip his hands in the gore of an after-dinner speaker? It would be like killing Father Christmas.”

In a previous post I wrote: My favourites are: “The Secret Garden”, “The Flying Stars”, “The Wrong Shape”, “The Hammer of God” and “The Three Tools of Death”. “The Invisible Man” and “The Queer Feet” are also worth reading. “The Blue Cross”, probably, the best known because it is the first Father Brown story, is highly overrated in my view. “The Honour of Israel Gow” and “The Eye of Apollo” are below average for my taste. And “The Sins of Prince Saradine” and “The Sign of the Broken Sword” are highly disappointing, in my opinion. By the way, it is said that Chesterton himself admitted to have written some of the worst mystery stories in the world.

However, my tastes have probably changed, and overall I have now enjoyed most of the stories. They are all worth reading.

The Innocence of Father Brown has been reviewed, among others, by Nick Fuller at The Grandest Game in the World, Edward D. Hoch at Mystery File, Aidan Brack at Mysteries Ahoy! Bev Hankins at My Reader’s Block and at FictionFan’s Book Reviews.

The Innocence of Father Brown has been included in Martin Edward’s The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, The British Library Publishing Division, 2017.

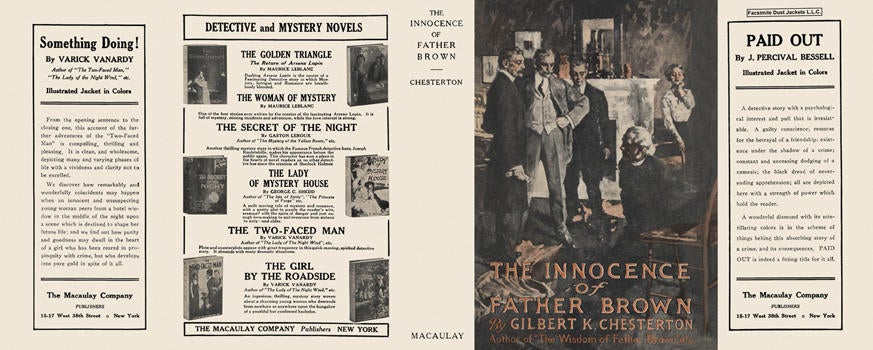

(Source: Facsimile Dust Jackets LLC.Macaulay (USA) c1919 reprint )

About the Author: Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was born in London, educated at St. Paul’s, and went to art school at University College London. In 1900, he was asked to contribute a few magazine articles on art criticism, and went on to become one of the most prolific writers of all time. He wrote a hundred books, contributions to 200 more, hundreds of poems, including the epic Ballad of the White Horse, five plays, five novels, and some two hundred short stories, including a popular series featuring the priest-detective, Father Brown. In spite of his literary accomplishments, he considered himself primarily a journalist. He wrote over 4000 newspaper essays, including 30 years worth of weekly columns for the Illustrated London News, and 13 years of weekly columns for the Daily News. He also edited his own newspaper, G.K.’s Weekly. Chesterton was equally at ease with literary and social criticism, history, politics, economics, philosophy, and theology. In 1930 he accepted Anthony Berkeley’s invitation to become the first President of the Detection Club, and participated in the Club’s activities with characteristic gusto.

His most popular character, the priest-detective Father Brown, appeared in 53 short stories, most of them compiled in five books, The Innocence of Father Brown (1911), The Wisdom of Father Brown (1914), The Incredulity of Father Brown (1926), The Secret of Father Brown (1927) and The Scandal of Father Brown (1935), and three uncollected stories: The Donnington Affair (1914) and The Vampire of the Village (1936) both included in later editions of The Scandal of Father Brown, and The Mask of Midas (1936).

About the Editor: Michael D. Hurley is a Fellow and Director of Studies in English at Robinson Collage, Cambridge. He has written widely on English literature from the nineteenth century to the present day, with an emphasis on poetry and poetics. His book on Chesterton, G. K. Chesterton, was published in 2012.

La inocencia del Padre Brown de G. K. Chesterton

Incluido en El Padre Brown de G. K. Chesterton con una introducción de Carlos García Rubio. Ediciones Encuentro, 2017. Formato del libro: Edición Kindle. Tamaño del archivo: 3948 KB. Longitud de impresión: 925 páginas. ASIN: B01MS5MXRH. ISBN: 978-84-9055-828-7. La inocencia del Padre Brown (traducción Alfonso Reyes) es la primera colección de relatos de G. K. Chesterton protagonizada por su cura detective. Loss doce relatos que componen esta colección se publicaron por separado en The Saturday Evening Post entre julio de 1910 y junio de 1911 antes de ser reunidas en forma de libro en 1911 por Cassell and Company Ltd., Londres, y por John Lane. Co., Nuevo

Sinopsis: El conjunto de los relatos del Padre Brown, escrito a lo largo de más de veinte años, constituye quizá la obra más popular de Chesterton. El simpático cura-detective que los protagoniza resuelve en ellos, armado únicamente con su paraguas, su inocencia y su sabiduría, intrincados casos gracias a un conocimiento sencillo a la par que profundo de la naturaleza humana. Frente a la destrucción sistemática de la razón, propia del escepticismo y el relativismo de la Europa de inicios del siglo XX, Chesterton crea este singular personaje –basado en su amigo el sacerdote irlandés John O`Connor y que es ya parte del imaginario de la cultura inglesa junto a otras figuras detectivescas como Sherlock Holmes o Hercules Poirot– para mostrar que sólo una mirada sincera y que reconozca el misterio que la realidad encierra es capaz de salvaguardar la razón. Además de los cinco relatos ampliamente conocidos, el presente volumen incluye otros tres que no aparecieron en las ediciones originales: “El caso Donnington”, publicado en The Premier Magazine, “La vampiresa del pueblo”, aparecido en Strand Magazine y probablemente el primer relato de una nueva colección, y “La máscara de Midas”, texto en el que Chesterton estaba trabajando cuando le sobrevino su enfermedad final en 1936.

Sinopsis: El conjunto de los relatos del Padre Brown, escrito a lo largo de más de veinte años, constituye quizá la obra más popular de Chesterton. El simpático cura-detective que los protagoniza resuelve en ellos, armado únicamente con su paraguas, su inocencia y su sabiduría, intrincados casos gracias a un conocimiento sencillo a la par que profundo de la naturaleza humana. Frente a la destrucción sistemática de la razón, propia del escepticismo y el relativismo de la Europa de inicios del siglo XX, Chesterton crea este singular personaje –basado en su amigo el sacerdote irlandés John O`Connor y que es ya parte del imaginario de la cultura inglesa junto a otras figuras detectivescas como Sherlock Holmes o Hercules Poirot– para mostrar que sólo una mirada sincera y que reconozca el misterio que la realidad encierra es capaz de salvaguardar la razón. Además de los cinco relatos ampliamente conocidos, el presente volumen incluye otros tres que no aparecieron en las ediciones originales: “El caso Donnington”, publicado en The Premier Magazine, “La vampiresa del pueblo”, aparecido en Strand Magazine y probablemente el primer relato de una nueva colección, y “La máscara de Midas”, texto en el que Chesterton estaba trabajando cuando le sobrevino su enfermedad final en 1936.

La inocencia del Padre Brown (conocido tambén como El candor del Padro Brown), una colección de doce relatos de misterio, apareció en 1911. Mientras que Sherlock Holmes se especializó en el razonamiento deductivo y utilizó ayudas científicas (huellas dactilares, microscopio y lupa) para investigar el crimen, el padre Brown es intuitivo. Confía en la filosofía y su conocimiento del pecado” (Martin Edwards en The Golden Age of Murder, Collins Crime Club, 2016).

Las doce historias que componen La inocencia del Padre Brown son:

“La cruz azul” (Publicado por primera vez el 23 de julio de 1910, bajo el título “Valentin sigue un rastro curioso” en The Saturday Evening Post y en septiembre de 1910 retitulado “The Blue Cross” en la revista The Story-Teller) Aristide Valentin, jefe de la policía de París, acaba de llegar a Londres para detener a Flambeau. Se sospecha que Flambeau, el criminal más famoso del mundo, se encuentra en Londres en donde espera cometer un crimen, aprovechando la confusión creada por la gran multitud de personas que asisten en esos días a la celebración del Congreso Eucarístico. Flambeau es un maestro del disfraz y puede hacerse pasar por cualquiera, si bien no puede ocultar su gran estatura. . “Valentin había logrado averiguar aquella mañana que un tal padre Brown, que venía de Essex, traía consigo una cruz de plata con zafiros, reliquia de considerable valor, para mostrarla a los sacerdotes extranjeros que asistían al Congreso. …. ¿Qué tenía en común el robo de una cruz de plata y piedras azules con el hecho de arrojar sopa a una pared? ¿Qué relación había entre esto y el llamar nueces a las naranjas, o el pagar de antemano los cristales que se van a romper? ((Traducción de Alfonso Reyes)

“El jardín secreto” (Publicado por primera vez el 3 de septiembre de 1910 en The Saturday Evening Post, luego en The Story-Teller, octubre de 1910) En una continucaión del relato anterior, la escena se traslada a París. Aristide Valentin, el jefe de la policía francesa, ha organizado una cena en su casa. El invitado de honor es Julius K. Brayne, un multimillonario estadounidense que está considerando donar una gran suma a la Iglesia Católica. La fiesta se interrumpe cuando uno de los invitados encuentra un cadáver en el jardín con la cabeza cortada. Nadie es capaz de identificarlo. Además, el jardín tiene paredes altas, no tiene puertas y no hay otra forma de entrar o salir del jardin sin ser visto mas que a través de la casa y la puerta de la casa estaba custodiada diligentemente en todo momento por un sirviente. En tales circunstancias resulta tan extraño establecer la identidad de la víctima como averiguar cómo llegó hasta allí sin ser visto. Todos los invitados son personas muy respetables y, excepto uno, todos tienen firmes coartadas. La única excepción es el propio Brayne, a quien se vio salir de la casa a toda prisa justo antes de que se encontrara el cadaver. Todas las sospechas recaen sobre él, pero la historia toma un giro inesperado cuando otro cuerpo decapitado aparece flotando en un río cercano, y su cabeza resulta ser la del propio Brayne.

“Las pisadas misteriosas” (Publicado por primera vez el 1 de octubre de 1910 en The Saturday Evening Post, luego en The Story-Teller, noviembre de 1910) “Si alguna vez, lector, te encuentras con un individuo de aquel selectísimo club de Los Doce Pescadores Legítimos, cuando se dirige al Vernon Hotel a la reglamentaria comida anual, advertirás, en cuanto se despoje del gabán, que su traje de noche es verde y no negro. Si —suponiendo que tengas la inmensa audacia de dirigirte a él— le preguntas el porqué, contestará probablemente que lo hace para que no le confundan con un camarero, y tú te retirarás desconcertado. Pero te habrás dejado atrás un misterio todavía no resuelto, y una historia digna de contarse. …. Si —para seguir en esta vena de conjeturas improbables— te encuentras con un curita muy afable y muy activo, llamado el padre Brown, y le interrogas sobre lo que él considera como la mayor suerte que ha tenido en su vida, tal vez te conteste que su mejor aventura fue la del Vernon Hotel, donde logró evitar un crimen y acaso salvar un alma, gracias al sencillo hecho de haber escuchado unos pasos por un pasillo. Está en cierto modo orgulloso de la perspicacia que entonces demostró, y no dejará de referirte el caso. Pero, como es de todo punto inverosímil que logres elevarte tanto en la escala social para encontrarte con algún individuo de Los Doce Pescadores Legítimos, o que te rebajes lo bastante entre los pillos y criminales para que el padre Brown dé contigo, me temo que nunca conozcas la historia, a menos que la oigas de mis labios.” (Traducción de Alfonso Reyes)

“Las estrellas errantes” (Publicado por primera vez el 20 de mayo de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post) “—El más hermoso crimen que he cometido —dijo Flambeau un día, en la época de su edificante vejez— fue también, por singular coincidencia, mi último crimen. Era una Nochebuena.” …. “Y Flambeau se puso a contar la historia del crimen, visto «por dentro», y aun visto por dentro resultaba cosa extraordinaria. Pues, por fuera, resultaba de todo punto incomprensible. Aunque es por fuera como debemos examinarlo los extraños.” (Traducción de Alfonso Reyes) La trama gira en torno a The Flying Stars, tres brillantes diamantes, cuya fama se ha extendido por toda Inglaterra, que son robados durante una inocente pantomima navideña.

“El hombre invisible” (Publicado por primera vez el 28 de enero de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post, luego en Cassell’s Magazine, febrero de 1911) Laura Hope le cuenta a John Turnbull Angus su complicada vida amorosa. Hace un año, mientras trabajaba en el pub de su padre, dos hombres le propusieron matrimonio. Uno era un hombre muy bajo llamado Isidore Smythe, el otro, alto y flaco, era James Welkin. No encontraba atractivo a ninguno de los dos, pero tampoco quería herir sus sentimientos. Para escapar de esta situación, les dijo que no se casaría con un hombre que no se hubiera abierto camino en el mundo y ambos se apresuraron a buscar fortuna, como si estuvieran en un cuento de hadas tonto, en palabras de la propia Laura. Un año después, Laura dirige un café, pero teme que Welkin la haya encontrado. Ella escucha su voz de vez en cuando cuando no hay nadie alrededor. Ha recibido una carta de Smythe, que ahora es un exitoso hombre de negocios pero, mientras lee su carta, sigue escuchando la peculiar risa de Welkin. Angus se ofrece a ayudarla poniendo el asunto en manos de un detective privado al que conoce y que vive cerca. El detective es Flambeau, el antiguo maestro criminal francés, ahora reformado por el Padre Brown. A medida que avanza la historia, Angus acompaña a Smythe a su apartamento y promete volver con Flambeau. Antes de irse Angus da instrucciones a cuatro personas, un limpiador, un portero, un policía y un vendedor de castañas, para que vigilen la entrada y le avisen si alguien entra en el edificio mientras él se ausenta. Cuando Angus regresa junto con Flambeau y el Padre Brown no hay nadie en casa de Smythe a pesar de que las cuatro personas a las que pidió que vigilaran la entrada le aseguran que nadie ha entrado o salido del edificio durante su ausencia. Poco después el cuerpo sin vida de Smythe aparece flotando en el río.

“El honor de Israel Gow” (Publicado por primera vez el 25 de marzo de 1911 como “La extraña justicia” en The Saturday Evening Post) En esta historia encontramos al padre Brown y a Flambeau, ahora detective privado, en el castillo de Glengyle en Escocia para ayudar al inspector Craven de Scotland Yard a resolver la extraña muerte y el secreto entierro del difunto conde, un hombre recluido que vivía como un ermitaño con su sirviente, el silencioso Israel Gow. El conde murió y fue enterrado en secreto por Gow. “Sin embargo, el último Glengyle cumplió la tradición de su tribu, haciendo la única cosa original que le quedaba por hacer: desapareció… Pero, aunque su nombre constaba en el registro de la iglesia, así como en el voluminoso libro rojo de los Pares, nadie lo había visto bajo el sol..” Con la única excepción de Israel Glow, su solitario sirviente. Por eso, los tres han venido a averiguar si realmente vivió allí, si realmente murió allí y si Israel Gow tuvo algo que ver con su muerte. “Suponga usted que el criado mató a su amo, o que éste no ha muerto verdaderamente, o que el amo se ha disfrazado de criado o que el criado ha sido enterrado en lugar del amo. Invente usted la tragedia que más le guste, al estilo de Wilkie Collins” ¿Cómo explicar las numerosas y enigmáticas pistas que se acumulan detrás de este suceso tan desconcertante? (Traducción de Alfonso Reyes).

“La forma falsa” (Publicado por primera vez el 10 de diciembre de 1910 en The Saturday Evening Post) “Una de las carreteras que salen por el norte de Londres se prolonga hacia el campo en un remedo de calle, donde la línea se conserva, aunque haya muchos huecos de terreno sin edificar. … El que pase por esta carretera no dejará de reparar en cierta casa que le llamará la atención sin que él mismo sepa por qué. … Todo el que pasara por allí el jueves anterior al domingo de Pentecostés, hacia las cuatro y media de la tarde, vería que se abría la puerta de la casa, y el padre Brown, de la iglesita de San Mungo, salía fumando su enorme pipa, acompañado de un amigo suyo, un francés llamado Flambeau, que fumaba también, aunque un cigarrillo diminuto. Estos personajes podrán tener o no tener interés a los ojos del lector, pero lo cierto es que no era lo único interesante que apareció al abrirse la puerta de la verde y blanca mansión. La mansión tenía otras peculiaridades que conviene describir, no sólo para que el lector entienda esta trágica historia, sino también para que entienda qué fue lo que se vio al abrirse la puerta.” (Traducción de Alfonso Reyes). Lo que sigue es la investigación de la muerte del célebre poeta Leonard Quinton, cuyo cuerpo ha sido encontrado en su estudio, junto con una nota que decía: “¡Muero por mi propia mano; sin embargo, muero asesinado!”. Hasta que el Padre Brown se da cuenta de que la forma de ese papel no es la correcta.

“Los pecados del príncipe Saradine” (Publicado por primera vez el 22 de abril de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post). ‘Cuando Flambeau cerró su oficina de Westminster para disfrutar un mes de vacaciones, decidió pasárselo a bordo de un bote de vela tan pequeño, que casi siempre lo manejaban a remo. … Flambeau, como verdadero filósofo, no tenía ningún propósito para sus vacaciones; pero tenía, como verdadero filósofo, un pretexto. O más bien, tenía un propósito a medias, y lo tomaba lo bastante en serio para que su éxito —si lo lograba— fuera la corona de sus vacaciones, y lo bastante en broma para que su fracaso —si tal acaecía— no las echara a perder. Hacía algunos años, cuando era el Rey de los Ladrones y la figura más notable de París, solía recibir extraños mensajes de aprobación, denuncias y hasta declaraciones de amor; pero uno de estos mensajes, entre todos, sobrevivía en su memoria. No era más que una tarjeta de visita, metida en un sobre que llevaba el sello de correos de Inglaterra. En el dorso de la tarjeta, escrito en francés y con tinta verde, se leía: «Si alguna vez se retira usted y se vuelve persona honrada, venga usted a verme. Tengo deseo de conocerle, porque he conocido a todos los grandes hombres de mi época. Esa jugada suya de coger a un detective para arrestar con él al otro es la escena más espléndida de la historia francesa». Y en el anverso de la tarjeta, con elegantes caracteres grabados, aparecía este nombre: «Príncipe Saradine, Casa Roja, Isla Roja, Norfolk».’ Un día, mientras el padre Brown se encontraba a solas con el príncipe Saradine, un bote de remos con seis hombres llega al embarcadero. Uno de estos hombres se identifica como Antonelli y se dirige al Príncipe Saradine con las siguientes palabras: ‘Cuando yo estaba en pañales, usted mató a mi padre y robó a mi madre. Mi padre fue el más afortunado. Pero usted no lo mató gallardamente, como voy yo a matarlo a usted…., y le doy a usted todavía una posibilidad que usted no concedió a mi padre. Escoja usted una espada.’ Para el Padre Brown ‘en este duelo hay algo todavía peor que el duelo. Lo adivino, aunque ignoro qué podrá ser?’

“El martillo de Dios” (Publicado por primera vez como “The Bolt from the Blue” el 5 de noviembre de 1910 en The Saturday Evening Post). El Honorable Reverendo Wilfred Bohun, un hombre muy devoto, se dirigía a la iglesia para sus oraciones matutinas cuando se encuentra con su hermano mayor, el Honorable Coronel Norman Bohun, quien de ninguna manera es un hombre devoto y tiene una relación adúltera con la mujer del herrero. El reverendo increpa al Coronel por su forma de vida mientras continúa hacia la iglesia a orar. Apenas ha pasado una hora y media cuando es interrumpido en sus oraciones por la noticia de que su hermano ha muerto. El coronel tiene el cráneo aplastado y junto a él hay un pequeño martillo. El padre Brown llega a la escena del crimen justo cuando las sospechas comienzan a caer sobre el herrero. El herrero, un presbiteriano acérrimo, tiene una coartada sólida y cree firmemente que la muerte del Coronel fue el resultado de un castigo divino. Sin embargo, el padre Brown está convencido de que el crimen fue cometido por la mano del hombre.

“El ojo de Apolo” (Publicado por primera vez el 25 de febrero de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post). Hercule Flambeau, detective privado, quería mostrarle al padre Brown su oficina ubicada en un edificio nuevo. El edificio era de estilo americano por su altura de rascacielos, aunque apenas estaba terminado y aún carecía de personal. Solo se habían mudado tres inquilinos; el piso justo encima de Flambeau estaba ocupado por un tipo que se hacía llamar el Nuevo Sacerdote de Apolo, cabeza de una nueva religión que adoraba al sol. El piso de abajo lo ocupaban dos hermanas que ofrecían sus servicios de mecanografía a terceros. Los otros pisos, los dos de arriba y los tres de abajo estaban completamente vacíos en ese momento. Después de una descripción más detallada de los ocupantes, ocurrió un suceso trágico. Pauline Stacey, una de las mecanógrafas, encontró la muerte al caer por el hueco del ascensor. ¿Sería un suicidio? ¡Imposible, dado el optimismo insolente de la muchacha! ¿Un asesinato? ¡Pero si en aquellos pisos casi no vivía nadie todavía!

“La muestra de la espada rota” (Publicado por primera vez el 7 de enero de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post) El padre Brown y Flambeau buscan en la tumba del famoso general inglés St Clair pistas sobre su misteriosa muerte. Arthur St Clair fue un exitoso e importante general inglés. Después de campañas espléndidas pero cuidadosas tanto en la India como en África, St Clair estaba al mando contra Brasil cuando el gran patriota brasileño Olivier emitió su ultimátum. St Clair, con una fuerza inglesa muy pequeña, se enfrentó a una fuerza brasileña mucho mayor, conduciendo a sus hombres hacia una muerte segura. Tras una resistencia heroica, St Cñair cayó prisionero. Después de su captura, y ante el horror del mundo civilizado, St Clair fue ahorcada en el árbol más cercano con su propia espada rota colgando de su cuello. El Padre Brown no puede entender por qué St Clair, uno de los hombres más inteligentes del mundo, actuó como un idiota sin razón, y Olivier, uno de los mejores hombres del mundo, actuó como un demonio sin razón. Debe haber algo desconocido que pueda explicar qué pasó.

“Los tres instrumentos de muerte” (Publicado por primera vez el 24 de junio de 1911 en The Saturday Evening Post) El padre Brown tuvo un sobresalto cuando, al amanecer, vinieron a decirle que sir Aaron Armstrong había sido asesinado. Había algo de incongruente y absurdo en la idea de que una figura tan agradable y popular tuviera la menor relación con la violencia secreta del asesinato. Porque sir Aaron Armstrong era agradable hasta el punto de ser cómico, y popular hasta ser casi legendario. … A petición de Patricio Royce, el enorme secretario ex bohemio, vinieron a llamar a la puerta del padre Brown. Royce era irlandés de nacimiento, y pertenecía a esa casta de católicos accidentales que sólo se acuerdan de su religión en los malos trances. Pero el deseo de Royce no se hubiera cumplido tan deprisa si uno de los detectives oficiales que intervinieron en el asunto no hubiese sido amigo y admirador del detective no oficial llamado Flambeau… Porque, claro está, imposible ser amigo de Flambeau sin oír contar mil historias y hazañas del padre Brown. Así, mientras el joven detective Merton conducía al sacerdote, campo a través, a la vía férrea, su conversación fue más confidencial de lo que hubiera sido entre dos desconocidos.

—Según me parece —dijo ingenuamente el señor Merton— hay que renunciar a desenredar este lío. No se puede sospechar de nadie. Magnus es un loco consumado, demasiado loco para ser un asesino. Royce, el mejor amigo del «baronet» durante años. Su hija lo adoraba sin duda. Además, todo es absurdo. ¿Quién puede haber tenido empeño en matar a este viejo tan simpático? ¿Quién en mancharse las manos con la sangre del amable señor de los brindis? Es como matar a san Nicolás.

En una entrada anterior escribí: Mis favoritos son: “El jardín secreto”, “Las estrellas errantes”, “La forma equivocada”, “El martillo de Dios” y “Los tres intrumentos de muerte”. También vale la pena leer “El hombre invisible” y “Las pisadas misteriosas”. “La Cruz Azul”, probablemente, la más conocida por ser la primera historia del Padre Brown, está muy sobrevalorada a mi modo de ver. “El honor de Israel Gow” y “El ojo de Apolo” están por debajo del promedio para mi gusto. Y “Los pecados del príncipe Saradine” y “La muestra de la espada rota” son muy decepcionantes, en mi opinión. Por cierto, se dice que el propio Chesterton admitió haber escrito algunas de las peores historias de misterio del mundo.

Sin embargo, mis gustos probablemente han cambiado y, en general, ahora he disfrutado casi todos los relatos. Vale la pena leerlos todos.

Sobre el autor: Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) nació en Londres, se educó en St. Paul’s y fue a la escuela de arte en el University College London. En 1900, se le pidió que contribuyera con algunos artículos de revista sobre crítica de arte y se convirtió en uno de los escritores más prolíficos de todos los tiempos. Escribió cien libros, contribuciones a 200 más, cientos de poemas, incluida la épica Balada del caballo blanco, cinco obras de teatro, cinco novelas y unas doscientas historias cortas, incluida una popular serie protagonizada por el sacerdote detective Padre Brown. A pesar de sus logros literarios, se consideraba ante todo un periodista. Escribió más de 4000 ensayos periodísticos, incluidos 30 años de columnas semanales para el Illustrated London News y 13 años de columnas semanales para el Daily News. También editó su propio periódico, G.K.’s Weekly. Chesterton se sentía igualmente cómodo con la crítica literaria y social, la historia, la política, la economía, la filosofía y la teología. En 1930 aceptó la invitación de Anthony Berkeley para convertirse en el primer presidente del Club de Detección y participó en las actividades del Club con entusiasmo característico.

Su personaje más famoso es el sacerdote detective Padre Brown. El Padre Brown apareció en 53 relatos, la mayoría de ellos recopilados en cinco libros, El candor del Padre Brown (1911), La sagacidad del Padre Brown (1914), La incredulidad del Padre Brown (1926), El secreto del Padre Brown (1927 ) y El escándalo del Padre Brown (1935), y tres relatos no incluidos en estas recopilaciones: El caso Donnington (1914), La vampiresa del pueblo (1936, ambos incluidos en ediciones posteriores de El escándalo del Padre Brown) y La máscara de Midas (1936) .

2 thoughts on “Notes On: The Innocence of Father Brown (1911) by G. K. Chesterton (revised August 20, 2023)”